Further material for Acquavideo 2021, Two-channel video installation, 4.1 audio system .

*digression around the origin of the title of Acquavideo 2021

please scroll down ︎︎︎

ACQUAVIDEO | Giorgio Mega

“There was a time when I thought a great deal about the axolotls. I went to see them in the aquarium at the Jardin des Plantes and stayed for hours watching them, observing their immobility, their faint movements. Now I am an axolotl.”

J. Cortazar, Axolotl, Final del juego (1956)

"Here's the kitchen, through this little window I once saw a wild boar, I immediately grabbed my rifle and BOOM, I splattered it nicely onto that cherry tree you see over there".

I remember very well the moment I first met F., a few minutes after getting off the bus. The appointment was in one of those pink little houses on the edge of the woods that would be my home for the next three years. "Oh, there's also a safe next to the fireplace; what do I know, if you’ve got a gun or something..."

F. spoke to us as if he had known us forever with a childlike smile on his wide cheerful face. The house was just what we wanted and the rent was affordable- deal.

The centre of Sabbioni is built on both sides of the Futa, around an inn (now called "Il Telegrafo", a bar, tobacconist's, tavern, games room, informal post office and small den for Bologna football fans), this since 1315. Apart from those few buildings (including the new church, low, wide, made of wood and stone, and the crumbling old one), a number of villas with gardens were built in more recent times, scattered towards the Idice valley to the east. These gardens on Via Verdi, Via del Pozzo and Via Napoleonica were home to a constellation of Dobermans, Rottweilers and Maremma shepherds. Then the woods again, mushrooms and wild boar. At the entrance of the village is a retirement home. The house where F. lived was at the other end, still on the Futa road, which on that side leads to Loiano, Monghidoro, and then to the watershed that divides Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany. At the time, the only shop in the village apart from the all-round tavern was a dimensional tear called Acquavideo.

It was F. 's lair, where a myriad of small artificial light sources criss-crossed between screens and coloured bulbs, a labyrinth of reflections, a kaleidoscope of questioning looks under glass and crammed shelves. The products on sale formed an unexpected but, to think of it, coherent mix: aquariums and video cassettes. To the left of the counter an anonymous yet heavy grey curtain separated this small space from an even smaller, deeper room, the pornography section. As a black hole in Sabbioni, Acquavideo concealed and manifested at the same time its obsession for observation. On the other hand, one of the clearest memories of my neighbours in those years was the curtains suddenly shutting when I would come home. Unlike, however, the person who lived in the little pink house to the right of my little pink house, an elderly man always sour and stiff, only picking porcini mushrooms and declining his gazing into spying through the window, F.'s desiring carnival looking with enthusiasm to the other watching itself, an archive of possible totemic animals in an atmosphere inclined to taboo. The cohabitation of so many small fish and other animals in varying degrees of presentability - there were also a few parrots, and rumours of pythons and iguanas or amphibians and who knows what else hidden somewhere beyond the visible - with a range of VHS from blockbuster to x-rated ones, was articulated in a cabinet of wonders of beings and objects more or less forbidden and more or less exposed.

I used to show up in this bizarre and tiny territory of desire and amazement once a month, cash in hand, to pay the rent. F. was almost always cheerful and cracked jokes out loud. Sometimes, however, he had a weirder expression where his good-natured cheerfulness was shadowed by despair. Perhaps this had something to do with the letter I received halfway through my stay in the Emilian Apennines. It was an official letter from the Court of Bologna notifying me that F.'s property had been seized and that from then on I would have to pay the rent into a bank account in the court's name.

I began to meet F. very rarely, in passing, and of everything I know about him I cannot remember what I was told first-hand and what by someone else. Around his life swirled a kind of mythical field in which absurdity and likelihood precipitated. It was perhaps F. himself who told me how the foreclosure came about because of a scam he had been involved in. He had been persuaded by a couple of foreigners to act as front man for a porn video shop in Bologna. These shady adventurers disappeared into thin air after doing crooked business with the video shop as a front, leaving poor F. in a lot of trouble. F. was obviously prone to leaps and bounds without a parachute, doomed to a daring and vitalistic failure. It certainly was not him - most probably L. - who told me about the time when a Neapolitan came to Sabbioni out of nowhere with a van equipped with a freezer, and about how he inexplicably convinced F. to take all the unsold buffalo mozzarella.

About twenty kilos of mozzarella.

L., by the way, was second to none in terms of legendary status, just think that he settled in Sabbioni starting from Marcianise as a small-time drug dealer, going through a real transformative epic that lasted a few years in Mexico, and arriving in the Bolognese mountains in the form of a hippie with an almost Franciscan outlook.

One day, the priest of the jogs approached him and, frowning, reported to L. that he had been told some alarming news by anonymous believers. He had been spotted going through the woods with a satanic pace and huge horns on his head. After days of wondering not only what they might think of him, but also through what powerful visions they saw him, L. realised that even if they hadn't exactly made the story up, there had been some imaginative distortion. As with Acquavideo’s glass and screens, there was a slight tendency towards illusion and metamorphosis. Most likely they had seen him return home with upturned roots on his shoulders, which he often used as a base for making wooden sculptures.

There were no devilish stories about F., but "rumours spread":

"You see that orange light flashing in the dark up there,

at F.'s house all night long?

That's the light to make the eggs hatch.

It makes them hatch faster,

and they come in all shapes and sizes!

Tropical birds.

Illegal reptiles.

It's the room where he sleeps, with those flashes, all night long!

There's his bed and these big egg cases.

And all around him, on the walls, Playboy posters...

and a big collection of guns."

Only now, thinking back of the room where he lived, do I realise a strange coincidence: a few years before hearing those stories, at the time I was an Art student in Bologna, I used to imagine impossible installations or 'situations', and one of them suddenly came to my mind, in one piece, like a vision: a club late at night, with orange strobe lights, half-finished cocktails on the tables, sticky floors and DJ sets still going strong, but there is not a single human in the place, only ostriches.

I've heard that F. no longer lives in Sabbioni, and that almost nothing is said about him in the village, at least not to strangers: "Ah, I wonder what happened to him?” And who knows what happened to those animals, or their offspring. In the Acquavideo, the metaphor of the dialectical vision between inside and outside the aquarium triggered the possibility of overturned perspectives. Neither have I lived in Sabbioni for many years now.

“I believe that all this succeeded in communicating something to him in those first days, when I was still he. And in this final solitude to which he no longer comes, I console myself by thinking that perhaps he is going to write a story about us, that, believing he's making up a story, he's going to write all this about axolotls.”

J. Cortazar, Axolotl, Final del juego (1956)

J. Cortazar, Axolotl, Final del juego (1956)

FACTS & FICTIONS | Ilaria Puri Purini

“Stretched forth the shell, so beautiful in shape,

In colour so resplendent, with command

That I should hold it to my ear.”

William Wordsworth, The Prelude (1799)

Like many romantics, I have always kept shells. I find them in random pockets and various bags of mine, reminding me of a form of encounter with the sea. The shell can be a frantic attempt to retain wonders of the underwater. As Wordsworth’s famous poem illustrates, the shell preludes to imagination, fantasies and dreams. A rotating shell on a dark background opens Michela de Mattei’s Acquavideo – as an invitation to listen to the sea and somehow stands as a reminder of the human desire to possess it, contained it, dominate it. An aquarium is ultimately an attempt to enclose the variety of the sea. It is a box where “animals and plants are kept for pleasure, study, or exhibition”, as the dictionary explains.

On the 25 February 2010 one of the tanks of the Dubai Aquarium leaked. Panicking people ran across the mall, were then quickly evacuated, and specialized operators were sent to repair what was defined as a technical fault. The video uses found footage of the unveiling of the glowing tank, adding to it an uncanny looping sound that stresses the excitement of this exhibitionism. The acid blues of the aquarium are contraposed to the luminous whiteness of the spaces of the mall, ‘no feeding the fish’ someone instructs insistently to groups of curious people trying to touch the fish. This voice starts to build a growing tension. The aquarium presents fragments of the underwater creatures: countless multicolor fish, octopus, sharks, a manta ray. A giant eel catches my attention; it seems to be going round and round in the constricted space of the tank. A mirroring screen reflects and multiplies the visions while a shrinking sound repeats itself. The images and the sounds are merged together into the same artifice. A siren alarm announces the overflow of water in the corridors of the mall, with their mesmerizing sound and hypnotic rhythm. The water quickly spills outside the tanks. On the right-hand screen an acid green fish appears. A rhythmic beat transitions the video into darkness, where fish appear and disappear, almost overlapping with each other, floating and swimming outside the aquarium. Then starts another dimension, one linked to immersion both physical and metaphorical. The obscurity envelops the viewer into the underwater of possibilities, fantasies and dreams. Fact and fiction, like the mall and the aquarium, collapse.

De Mattei’s work underlines how the Dubai Mall is an extreme place of consumerism containing not only the infinite possibilities of objects but also the wonders of the underwater. The double screen emphasizes the contradictions and the similarities between the two containers: the mall with its shops and the tanks with its fish. Luminous brands and glowing tanks are juxtaposed to images of marine creatures, an exasperated visibility that is almost aching to the eyes. Lights, people, fish, tanks, shops and sounds mix and merge together. The overlapping imagery strengthens the relationship between consumerism and wonder, the desire to both possess and dominate sea life that is impossible to contain. As the video escalate into darkness, other senses are addressed. Like under the water, it’s not so much about seeing anymore but about feeling and hearing, these are the references of being immersed. Philosopher Emanuele Coccia defines immersion “like a jellyfish which is no more than a thickening of water”, and so feels the viewer of Acquavideo becomes a diver, enveloped and at one with its aquatic dimension.

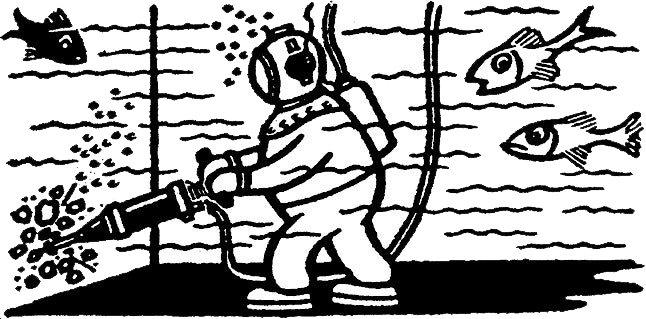

The cartoon above shows a diver in a fish tank, drilling its glass structure. The fish seem to be surprised by this intrusion, as if wondering that he is going and what will happen to them. Is the diver letting the fish out or is he destroying the tanks? The irony of this image makes us consider the paradoxes of leak of the Dubai Mall. The leak was an accident, a fault in the complexity of acquariums, a mistake made by humans. But I like to think about it also in terms of humor and unlikelihood: an attack on the Dubai Mall and its consumerist western capitalist values. The quote at the beginning of the video hints towards this interpretation: “who will heal the fish from their muteness? they cannot praise the lord with their song they cannot confess their faults through their voices.” Taken from the Bible, the quote refers to the impossibility of the fish of not being able to confess, in a purely catholic way, their responsibilities on the attack. Yet, they are not flawless as the found video of the reporter concludes “no human or fish were harmed”. Situating the animal and the human realm on the same level, this quote actually subverts the standpoint of the point of view. Whose point of view are we considering?

De Mattei plays between facts and fiction, and seems to give agency to the fish. By blurring the boundaries of what is given and what might be, Acquavideo introduces the perspective of the fish, inserting ethical questions relating to aquariums and criticizing the excesses of capitalism. Scientific studies suggest that fish do feel pain when caught, and confronted with their display in tanks, we wonder about the consequences to being exposed to such continuous artificial light. These considerations on aquaria shift the work from the Dubai Mall into a broader discourse on the Anthropocene, reflecting on how human activity has a significant impact on marine ecosystems. By doing so it also calls for an awareness on ethical treatments of fish and the human need to consider the quality of life of other species.

Towards the end of Acquavideo a man is dancing or perhaps performing on a rocky mountain. The mountains offer a strong opposition to the fish and watery visions dominating the video. This mystical figure seems to stand as a reminder of the need of balancing opposites; rocks and shells, men and fish, malls and tanks, human and nature. There seems to be a human duty in considering the point of view of fish, especially in the current climate crisis that sees marine ecosystems at risk of being destroyed.

︎︎︎back